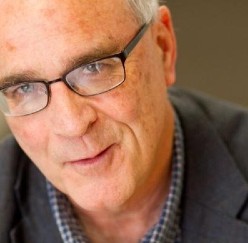

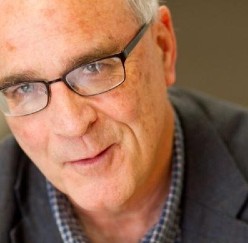

Library Thought Leader Bob Nardini Retires after 40-Year Career

From resident volcano expert to approval plan designer, Nardini has held just about every role the profession has to offer

By Alison Roth

If you work in or near the library world, there’s a good chance you know Bob Nardini. And even if you don’t know Nardini, you still know him. You might’ve seen him present at a conference – he’s been a longtime regular on the speaking circuit at events like Charleston and ER&L – or you’ve read his writing in the Scholarly Kitchen, Against the Grain, or the ProQuest blog. Or, even more likely, you’ve somehow interacted with Nardini during his long career working for library vendors, including YBP (now GOBI), Ingram, Coutts and ProQuest, Part of Clarivate.

Nardini turned in his ProQuest badge on New Year’s Eve, retiring after nearly 40 years in the field. His departure will not only be felt at the company, where he last served as Vice President of Library Services, but from every corner of the industry. “Bob has made a tremendous impact in the academic library space during his 15 years with us and throughout his entire career,” said Oren Beit-Arie, who led the ProQuest books business. “I’m excited for Bob’s next journey, but will also miss him dearly.”

Nardini turned in his ProQuest badge on New Year’s Eve, retiring after nearly 40 years in the field. His departure will not only be felt at the company, where he last served as Vice President of Library Services, but from every corner of the industry. “Bob has made a tremendous impact in the academic library space during his 15 years with us and throughout his entire career,” said Oren Beit-Arie, who led the ProQuest books business. “I’m excited for Bob’s next journey, but will also miss him dearly.”

From customs to the reference desk

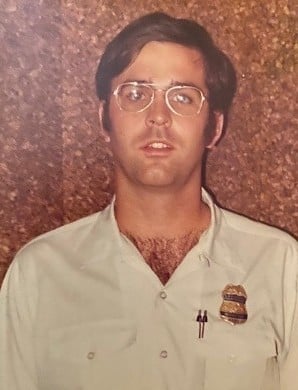

Nardini didn’t exactly take a traditional path to becoming a librarian. After graduating from Syracuse University with a degree in social studies education and history, he got a job in Toronto as a customs inspector. During his time working in customs, where he recalls once clearing Muhammad Ali at the Toronto airport, Nardini decided to apply to graduate school.

“I had always liked being in libraries and using libraries. I had no other career ideas, so I picked library school,” he told ProQuest in an interview just before his retirement. He applied to the University of Toronto but was waitlisted, so he took a transfer to the customs office in Champlain, New York, a town on the far northern border of the state, just below Montreal.

“Those customs years were mainly drudgery, but they did enable me to save enough money for library school,” Nardini said. “One other officer in Champlain had begun library school, but he didn’t finish. I may be the only person in history to make the career transition from customs officer to librarian.”

Customs, said Nardini, maintains an elaborate scheme for classifying just about anything you can think of to apply duties – just like the systems librarians have for classifying books. “I can’t think of any other similarities between the two fields,” Nardini admitted. He applied to the University Toronto a second time, in 1977, and this time, he was accepted.

Volcano fatigue

During and after graduate school, Nardini worked at libraries all over the map, literally and figuratively. He was a summer associate at the Canadian Paraplegic Association, an intern at McMaster University in the library’s government documents department (“I never did understand the way the United Nations organized their records,” he confessed) and a reference librarian at the public library in Charlottesville, Virginia, right next to a now-defunct statue of confederate general Robert E. Lee. From there, Nardini took a role as a reference librarian at Concord Public Library in Concord, New Hampshire, where he compiled the library’s historical materials collection register.

“At first I loved working on those reference desks, a seat that gives you a view of your city you might not get any other way,” Nardini said. But after several years in Concord, he was burnt out. Each season, he dreaded the annual “volcano assignment” at the local public school, where students were assigned a volcano to research. Some, he mused, cared much more about their volcanoes than others.

“This was pre-internet, of course, and a minor volcano might have just one article about it in our modest collection, in a National Geographic issue you knew you’d fished out of the basement in the past, with the help of the Readers Guide to Periodical Literature,” he said.

After one too many volcano queries, Nardini responded to a newspaper job ad from Yankee Book Peddler (now GOBI), a company selling books to academic libraries located nearby. He got a job as a bibliographer and stayed there for more than 20 years, eventually put in charge of defining, maintaining, and marketing the company’s approval plans – a job he did so well that many of those programs continue to exist.

Librarians as vendors

“I think a lot of librarians don’t realize that you can have a rewarding career working for one of the companies who serve libraries,” said Nardini. “These businesses benefit from the expertise librarians bring to the job, but even more so from having staff who understand the values and can talk the language of librarians.”

True to those words, Nardini spent the remainder of his career working for the companies who serve libraries. He continued his approval plan work at Coutts (now ProQuest) where he was instrumental in the development of the OASIS ordering database.

Nardini’s vendor career allowed him to continue doing the things that he loved – no volcanoes required. He represented his employers by speaking at conferences and through writing and publishing articles. He oversaw book selection for ProQuest’s two big opening day library collections in the Middle East – the Muhammad bin Rashid Library in Dubai and House of Wisdom in Sharjah. Before retirement, Nardini consulted on the development of Rialto, helping gauge interest among librarians and listening to their advice on what a new book selection and ordering system should be able to do. “I consider it good fortune that I’ve always had the chance to work in different parts of the business,” Nardini said.

And no matter what role he held, he just couldn’t get away from approval plans. In fact, he wrote the encyclopedia entry “Approval Plans” in the Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. Years later, he led an intriguing Charleston presentation entitled Approval Plans: An Apology, reflecting on the need to radically change approaches to collection development in today’s libraries.

“Bob never stops looking for ways to evolve and advance the profession,” said Beit-Arie, “including his own ideas.”

A long-evolving business

Nardini has worked in the industry for long enough that he’s seen things change, change again, and in many cases, change back to where they were before. When he started at YBP, said Nardini, it wasn’t unusual for publishers to sell their books directly to libraries. That practice was nearly eliminated with aggregation, returned with the popularity of ebooks, and it’s now common for libraries to buy content from a combination of publishers and aggregators.

Something else that turned everything on its head, he said, was Amazon. “Amazon basically changed the rules for publishers and expectations about speed of delivery for everyone,” Nardini said. “Amazon earns credit – I think even its critics would agree – for setting the bar on metadata so much higher than it once was: that is, skimpy, too early or too late, hard to find, often inaccurate.”

Through it all, Nardini continues to admire the determination and the ingenuity of the small independent publishers who’ve managed to build a niche for themselves and continue to compete with the big players. That’s part of the reason he devised the popular Appreciating Smaller Publishers blog series in 2021, which continues into this year.

Sage advice

Naturally, we asked Nardini what parting advice he’d offer to libraries and vendors today. Among his gems, one stood out: libraries, he said, have the unique role of preserving the record of our culture, and they should do a better job of owning that critical responsibility.

“Over time, libraries have preserved culture by what’s written on the page, and now, they’re learning how to do the same thing for what’s ‘written’ on a screen,” Nardini said. “I’m sure what might have seemed to be some individual’s crazy passion is now saved as a treasure. I don’t think the value of this is widely enough recognized or rewarded – even by libraries themselves at times. I think libraries could do better at promoting this role of theirs.”

If you’re one of the thousands – maybe even tens of thousands – of colleagues, librarians and users who have crossed paths with Nardini, consider yourself among the lucky ones. In spite of his own successful career, Nardini prides himself on having mentored and guided other people. He’s helped so many build their careers, build their collections, and find exactly what they’re looking for.